“I don’t take the Bible literally, I take it seriously.” // “I’m not a covenant theologian because I read the Bible literally.” // “We’ll know when Jesus is coming back, because the prophets tell us literally what will happen.”

There’s no shortage of quips about the relationship between the Bible and “literal” interpretation. But in an age when “literally” can literally start every sentence, what does that word even mean anymore? Literally, I don’t even know anymore.

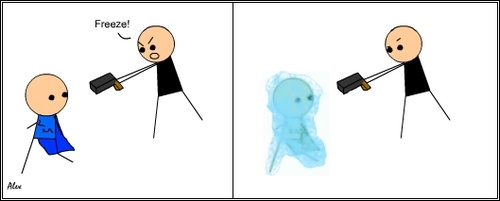

I’m always a sucker for a fantastic illustration. In Iain Provan’s new The Reformation and the Right Reading of Scripture, he uses the amusing series for kids, Amelia Bedelia, to explain the problem with what many people mean when they say we should interpret the Bible literally.

In these stories, which I’ve recently been reading to my three year old, Amelia receives instructions that she consistently interprets completely literally. That is, she does not understand figures of speech or contextual instructions. To “dust the furniture,” she adds dust to it. To make a sponge cake, she adds sponges. The results are often comical, potentially dangerous (seriously her babysitting stint is a bit terrifying), but always result in a happy ending.

The problem with Amelia Bedelia is that she doesn’t understand communicative intent. We must understand the context in which a phrase is spoken, of if it is written, the historical context that gave rise to its composition and the literary context that gives us so many clues to meaning. We must understand speech acts, by which communicators use words to “do” or “perform” (e.g., saying “I’m cold” isn’t strictly to communicate the fact, but is a request to turn up the heat). We must understand figures of speech, genres, and communicative goals.

All these factors go into interpreting a clause, but that doesn’t mean we’re out of the realm of the literal. Consider Jesus in John 6. When he says “Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him” (John 6:56), is he demanding cannibalism? That would be the “literal” interpretation, according to some peoples’ standards. No, of course not. Jesus is literally using a figure of speech. If we can’t be sure of Jesus’ communicative intent when we read v. 56, we continue in the literary context to see that Jesus compares himself to Israel’s manna. The Israelites died after eating their manna, but “whoever feeds on this bread [i.e., Jesus’ body] will live forever” (6:58).

Jesus’ disciples are still hanging in the realm of the obliviously-literal and ask “This is a hard saying; who can listen to it?” (6:60). Jesus then clarifies for them: “It is the Spirit who gives life; the flesh is no help at all. The words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life” (6:63). Jesus corrects them for taking him literally in the wrong sense, and provides them with the proper framework to understand his communicative intent, which includes the (literal) symbolism of Jesus’ body as life-giving, eschatological manna.

Provan summarizes his view of “literal” nicely. He says reading literally means

to read [Scripture] in accordance with its apparent communicative intentions as a collection fo texts from the past, whether in respect to smaller or larger sections of text. It means to do so taking full account of the nature of the language in which these intentions are embedded and revealed as components of Scripture’s unfolding covenantal Story–doing justice to such realities as literary convention, idiom, metaphor, and typology or figuration. To read literally is, in other words, to try to understand what Scripture is saying to us in just the ways in which we seek to understand what other people are saying to us–taking into account, as we do so, their age, culture, customs, and language, as well as the verbal context within which individuals words and sentences are located. This is what it means to read “literally,” in pursuit of the communicative intent of God–in search of what to believe, how to live, and what to hope for. (Reformation and the Right Reading of Scripture, p. 105)

Provan’s 650-page tome argues that the NT authors and the Reformers interpreted the Bible literally, and we can follow their lead, even while sharpening our hermeneutic with today’s critical tools.

Learn more about Provan’s book from us, or buy it on Amazon.

2 comments