If you’re a sharp reader, you noted the ambiguity in the title: do I mean that this book is for everyone and is about the KJV, or do I mean that this book is arguing that the KJV is for everyone? Yes.

As I lectured a few months ago on the biblical canon and authority, I was asked as one of the final questions, “What do you think about the KJV?” What a way to end the night! I did my best to avoid all controversy in order not to distract from the main subject at hand, but it goes to show you that the question is common enough. Anyone with any experience with a KJV-onlyist also knows that the discussion can get fiery and often out of hand.

Mark Ward’s new book, Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible, is now going to sit in my arsenal (i.e., my library), awaiting its deployment as an informed, lightly humorous, and irenic discussion of the merits and problems with using the KJV as one’s main or only Bible translation. Want to know what I think about the KJV? Read this book!

Ward grew up as a KJV reader, memorizing it and even learning to speak its language. He’s therefore a great candidate to find a balanced perspective on this controversial translation. In Authorized, Ward argues that the major deficiency with the KJV today (but not when it was translated) is that many words have fallen out of use or have even become false friends because of the words’ shift in meaning from 1611 to today.

He gives a multitude of examples from specific passages in which words are used that the modern reader (myself included) cannot understand without doing the necessary etymological work with the Oxford English Dictionary. Helpful are the numerous personal anecdotes about memorizing passages whose meaning he confesses not to have understood.

The strongest point Ward seems to want to make is that the Bible is intended for the vernacular language, not for some high, elitist literary register of a language. He notes correctly that the Koine Greek of the Bible was the lower register of Greek, as was the Septuagint’s Koine. I agree when he says, “a Bible translation’s language should be universally intelligible It should sound recognizably current, not antiquated on the one hand or edgy on the other” (69).

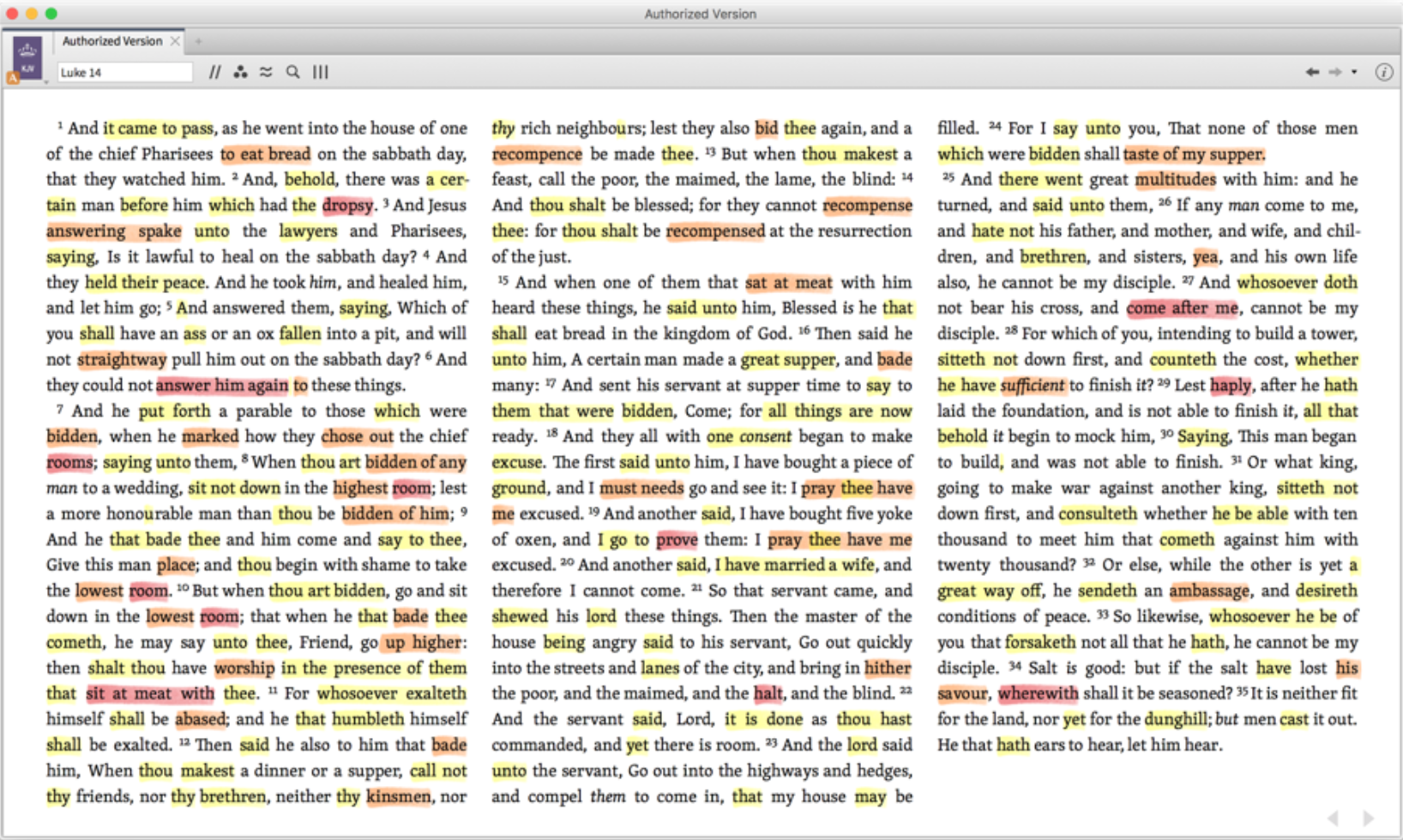

An example of how creative and engaging Ward’s book is comes from this same fifth chapter where he provides images of a “vernacular heat map.” Figure 1 shows the heat map for the KVJ of Luke 14. Yellow highlighting shows antiquated constructions that can be mastered by consistent KJV immersion. Orange highlighting shows are antiquated constructions that could possibly become familiar through KJV immersion. Red highlighting shows antiquated words or constructions that will likely be not understood or (worse) misunderstood.

Figure 1: Heat map of Luke 14, KJV, by Mark Ward

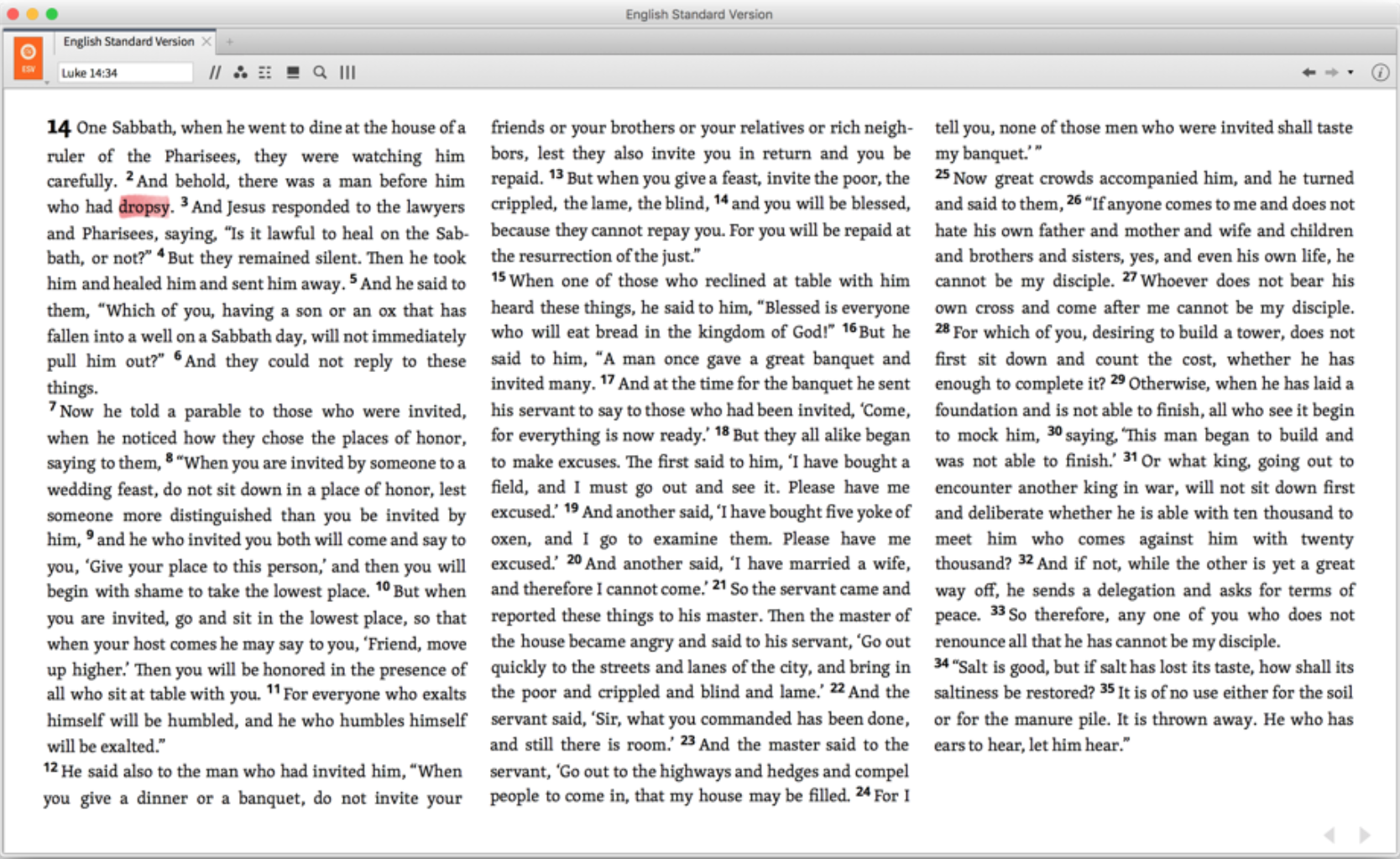

By contrast, Figure 2 shows a heat map of the ESV, which contains only one red highlight for the word “dropsy,” for which a modern reader would need to consult an English dictionary (it means modern edema).

Figure 2: Heat map of Luke 14, ESV, by Mark Ward

Ward works his way around, circling in on his main point, which he finally reveals at the end of chapter five, before defending his argument in chapters six and seven. Striving to maintain value in the KJV, but also striving to demonstrate the value of modern vernacular translations, Ward concludes:

In countless places, the KJV does not fail to communicate God’s words to modern readers; I’m eager to acknowledge this fact, because I grew up on the KJV and it was God’s tool to bring me new life. But in countless places, it does fail–through no fault of the KJV translators or of us. It’s somewhere between Beowulf and the English of today. I therefore do not think the KJV is sufficiently readable to be relied upon as a person’s only or main translation, or as a church’s or Christian school’s only or main translation (p. 85).

I found Ward’s presentation throughout the book to be tactful, tasteful, balanced, and winsome. If anyone is able to win KJV-onlyists to see the value in vernacular translations, it might be Ward. If anyone is able to demonstrate that the KJV still has value, it might be Ward.

In chapter six, he provides ten objections to reading Vernacular Bible translations to defend his thesis. Some objections are more forceful, but some are rather bland (which makes Ward’s defense easier), but all are objections Ward has encountered.The seventh chapter is also a useful answer to the oft-asked question, “Which Bible Translation is Best?” I won’t give away Ward’s answer, but it’s a useful chapter for anyone who is asking the question, and a chapter I would endorse as being in-line with my own views.

Overall, Authorized is a great read. It’s informative, winsome, clear, concise, and a handy book for those wondering about the KJV and modern Bible versions. I recommend it highly.

Hear more from Mark Ward on our Tool Talk interview.

Buy Authorized on Amazon.