“I wish to remind you, although you once learned fully, that Jesus,

after saving a people out of Egypt,

afterward destroyed those who did not believe.” -Jude 5

Who Destroyed the Israelites?

One of the most hermeneutically significant textual variants in the NT is in Jude 5, where someone destroys the Israelites. The reference is to Israel’s 40-year sentence in the wilderness, where all those above the age of 20 had to die before he could bring Israel into the promised land (Num 14:29). The severity of Jude’s verb “destroyed” might also refer especially to God’s judgment on rebellious Israelites during this time period, such as Korah and company, who get a special mention in Jude 11.

This seemingly typical reference to OT history is electrified by the fact that many manuscripts say not that God or the Lord destroyed the Israelites, but that Jesus did! Older translations always chose “the Lord” as the best reading, so that Jude was saying the Lord destroyed the Israelites (KJV; NASB; NAB; NRSV; NIV; RSV has “that he who saved a people…,” following a conjectural emendation by Hort).

The tides have turned, though. Three major English translations have recently chosen the reading “Jesus” (ESV; NET; NLT), as have the three major critical Greek editions: NA28 (27th ed. chose “Lord”), UBS5, and Tyndale House Greek New Testament.

Checking the Apparatuses

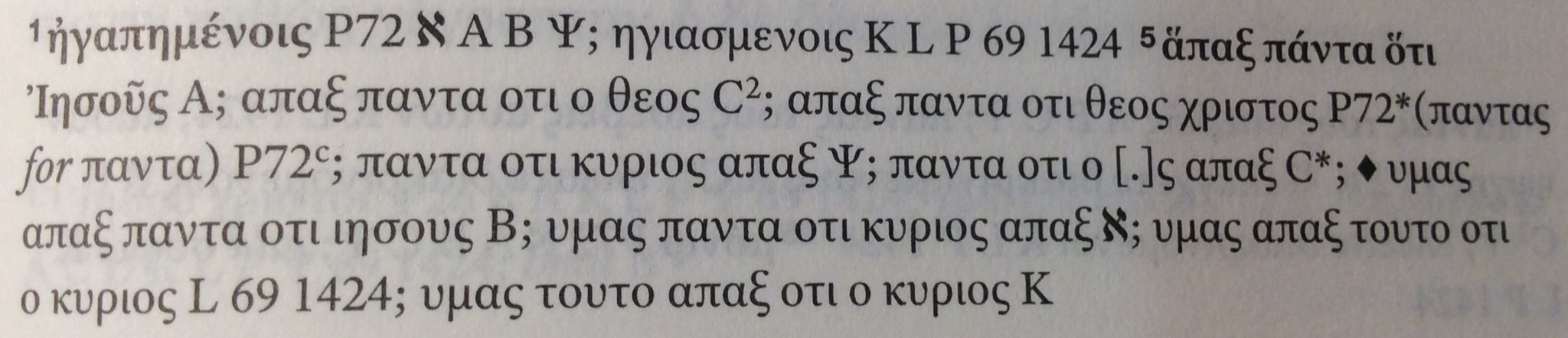

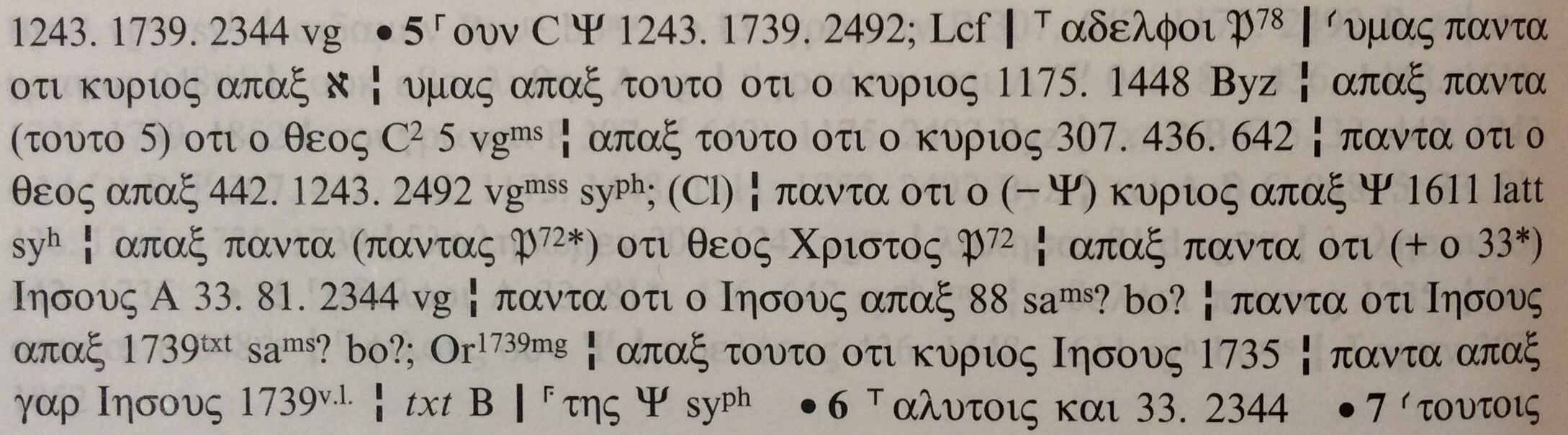

While the THGNT has a much smaller apparatus than the NA28, it does include more information for important variants such as Jude 5. Both apparatuses are included for comparison.

THGNT Apparatus for Jude 5

NA28 Apparatus for Jude 5

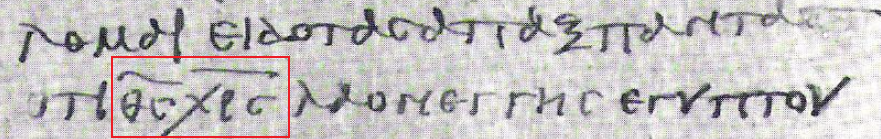

As you can see, the evidence is difficult to judge. The earliest reading is actually from the 3rd-4th century in P72, which contains θεος χριστος but written as nomina sacra (θς χρς).

Jude 5 in P72. Screenshot taken from http://csntm.org/manuscript/View/GA_P72.

Other early, important readings include:

- κυριος (א, aka Sinaiticus, 4th cent.)

- ο θεος (2nd corrector of C, 5th cent.)

- Ιησους (A and B, aka Alexandrinus and Vaticanus, 5th and 4th cent. respectively

What a mess! There are four different readings in the five earliest and most reliable manuscripts. Moreover, one can see from the NA28 apparatus that there are a multitude of readings that evolved in the later manuscripts, some adding articles, some dropping or rearranging words around the name in question, and so forth. I like the THGNT apparatus here because it gives the most significant readings and only refers to a few late mss from the 9th and 10th cent, thus showing their commitment to basing their decisions on early manuscripts.

What’s the Best Reading?

This variant has always greatly intrigued me. Without having covered the secondary literature extensively, I agree with much of P. Bartholomä’s analysis.

P. Bartholomä argues from the perspective of reasoned eclecticism that ᾿Ιησοῦς is the best reading (NovT 50, no. 2 [2008]: 143–158). Externally, the reading ᾿Ιησοῦς is more widespread, being in Egypt/North Africa and the Western Empire in the first few centuries. Contextually, Jesus is called “master” in v. 4, a term used for the Father (Luke 2:29; Acts 4:24; Rev 6:10), so a high Christology is already evoked, which makes the high Christology of an ᾿Ιησοῦς reading in v. 5 plausible. A very similar concept of Christ’s pre-existent involvement in the Exodus is likely present in 1 Cor 10:1–11 as well. It seems more likely that scribes would feel more uncomfortable with ᾿Ιησοῦς than with κύριος and change the former to the latter.

But, as Bartholomä argues, the reading is not too hard. If 1 Cor 10 does present Christ as involved in the Exodus event, we have a conceptual parallel, and we can perhaps see the pre-existent Christ also in Heb 11:26 and John 8:58 (and perhaps 1 Pet 3:22 is a parallel to Jude 6, which says the subject of the one who destroyed the Israelites also kept the rebellious angels in chains). While we cannot be absolutely certain, ᾿Ιησοῦς does seem to be the best reading, as the most recent critical Greek editions have decided (NA28, UBS5, THGNT). While some consider the idea too difficult, we should not be surprised. If God is a Trinity, then God the Son was always present throughout OT history, even if we are not exactly clear on his role or actions.

One of the strangest aspects of v. 5 is that Jude says “Jesus” (assuming that is what Jude wrote) rather than “Christ” or “the Son.” It is strange for two reasons. First, Jude everywhere else refers to his brother as “Jesus Christ” (Jude 1, 4, 17, 21, 25). Admittedly, it is odd he would then in v. 5 only refer to his brother as “Jesus,” but if we also admit that much of Jude relies on pre-existing material, then perhaps he was only following his source. Also, Jude is such a short epistle that we cannot reasonably make any arguments based on style; he was not a slave to his own expressions.

Second, it is odd that he would refer to “Jesus” as active in the OT, since Jesus was the name of the man, incarnated more than a millennium after the Exodus. But Jude was the brother of Jesus and knew him by his human name. We might consider this anachronistic reference akin to saying “President Bill Clinton became governor of Arkansas in 1978.” Of course, in 1978, he had not yet been “President Bill Clinton,” but from our perspective we now refer to him as such because “President” has become wrapped up in his identity. Likewise, even when referring to the pre-incarnate God the Son, Jude could not help but refer to him as Jesus, the name he used for his brother all his life.

Summing Up

This blog post is not intended to solve all the mysteries of Jude 5, or to conclusively argue for the correct reading. I merely wanted to discuss a favorite variant of mine, brought to mind as I was working through the THGNT with its unique textual-critical approach. I believe “Jesus” is the right reading here, and believe the Son of God was active everywhere “Yahweh” was active in the OT (to some extent), since the Trinity has always been a Trinity. To suggest otherwise is to live in the “world of the text” as if it were the only world that existed.

Don’t quit now! There’s 24 other verses in Jude to scrutinize closely in Greek. Dig in to the entire epistle–in Greek–in our Jude Greek Reading Videos. We’ll walk you through the vocabulary, syntax, and some uses of the OT and Second Temple Jewish literature.