My college days were full of takeout, and I had a go-to menu item for every restaurant. Chinese food for lunch? I’ll have the Springfield Cashew Chicken. Night out with the guys? Boneless wings, please. Need to grab something quick? Chick-Fil-A never disappoints.

One day I had an epiphany: I really just love fried chicken chunks, of any variety. (And, let’s be honest, there’s still plenty of takeout in my life.)

That’s a little bit like good preaching.

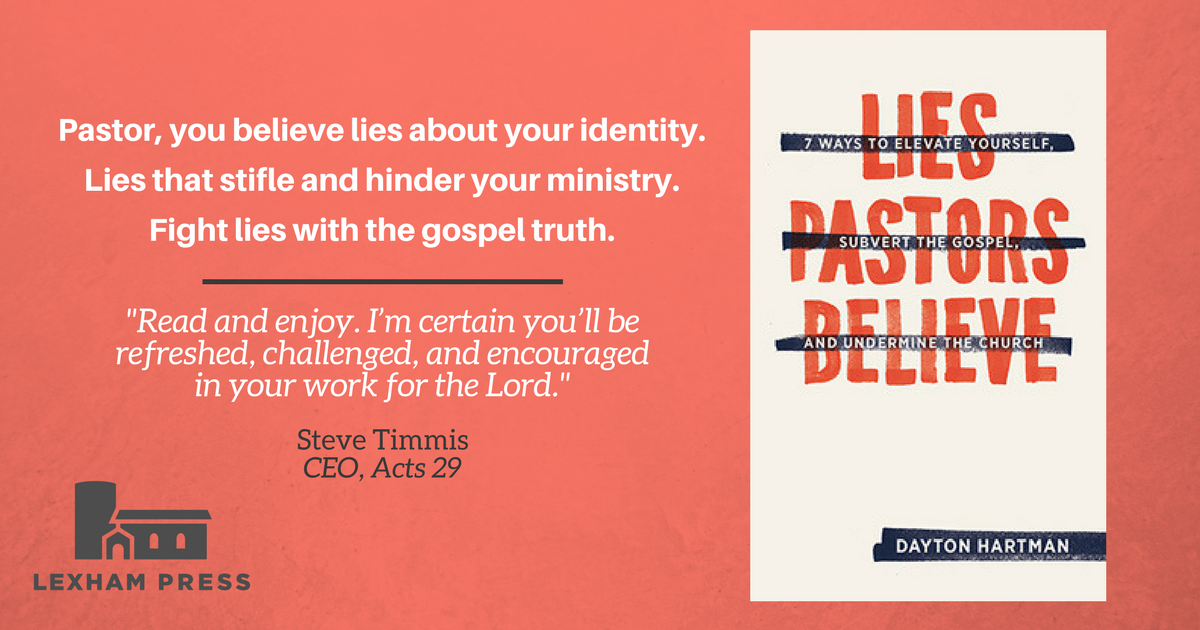

In Dayton Hartman’s new book, Lies Pastors Believe: Seven Ways to Elevate Yourself, Subvert the Gospel, and Undermine the Church, he lays bare the dark parts of a pastor’s heart and applies the Gospel scalpel.

No matter how you slice it, preaching is a deeply personal act. It’s also a deeply performative act.

One of the greatest dangers for a preacher is that his performance becomes the focus, and the situation is perhaps most dire when his performance is met with applause.

Hartman tells his own story:

A few years after seminary, the lessons I learned from all those hours watching Iron Chef were still with me. In one of my ministry assignments, I preached a sermon that elicited far more praise than it deserved. Numerous congregants approached me and told me things like, “You are so gifted! You need to preach here more often!” Others said things like, “No one has ever fed my soul like you!” I took it all in and believed every word of it. Just like on Iron Chef, the presentation makes all the difference. And I thought I was good at it! (15-16)

But the praise was short-lived. Familiarity may not always breed contempt, but it can certainly desensitize. After a while, one particular congregant — who gave the highest praise — was revealed to have nefarious motives, sowing discord between the pastoral staff.

This led Hartman to pore over sermons from some of the most well-known and respected preachers of our day, to learn as much as he could about what makes a truly great message.

What did he find? Hartman writes,

What made their sermons so good is that they all used the same ingredients: Christ-centered exposition, a high view of God, and a hearty helping of scandalous gospel grace. The only difference was in how they assembled and presented the ingredients. It turns out good sermons aren’t like Iron Chef after all. The key isn’t the style or manner of presentation (although that is important); the key is the ingredient list! (19)

Good sermons are defined more by substance than style: Christ-centered exposition, a high view of God, and a hearty helping of scandalous gospel grace. Share on X

So let’s all bone-up on our Christ-centered hermeneutic. Lesson learned, right? Well, maybe there’s more we can do.

Through the rest of the chapter, Hartman lines out some practical helps — think of them as guardrails — to keep pastors from believing the lie that their performance makes the decisive difference.

His most compelling challenge? Weekly sermon review — with a group.

It’s one thing to listen back to a recording of your message, but it’s another thing to open yourself up to critique.

But those tasked with preaching are called of God to do their very best “to present [themselves] to God as one approved, a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth” (2 Tim 2:15).

Citing the encouragement of Mark Dever of Capitol Hill Baptist Church and 9Marks, Hartman describes his process:

Our church has instituted weekly reviews of each Sunday’s sermon, and it has produced exactly what Dever promised it would: clarity in gospel communication. Each Thursday, our staff and interns meet to review the sermon manuscript for the message to be delivered on Sunday. Then, on the following Tuesday, we review the message that was delivered. (23)

“The benefits of this practice are numerous,” Hartman writes. Here’s what he and his church have seen since beginning sermon review:

- Sermon review increases Gospel clarity. The variety of personalities, life situations, and experience help to ensure that the meat of the message is being communicated in a way that can be understood.

- Sermon review makes your sermons better. The same variety that increases clarity brings out diverse application and illustrations.

- Sermon review produces humility. Hartman writes, “[I]nviting critical feedback and comments seems like madness, but it isn’t. It only serves to encourage your heart and to produce increased humility before your people and your leadership team. We all need more humility” (24).

- Sermon review builds good preachers. This is precisely the kind of practice that seminarians and interns go through as they are learning how to preach well. Why not you, seasoned veteran? Sure, you’ve honed your skills over the years, but you’re not perfect yet, right? Open yourself up to review and see how you might benefit from collaboration.

Whether it’s reviewing your sermon afterwards or digging into exegesis beforehand, everyone who preaches or teaches the Word can stand to be reminded of this truth: Whatever our style and however immense our gifts, we can all grow as we declare the truth of Christ in a world of lies.

Want to read more about Hartman’s story? Curious what other guardrails you can put in place to protect your ministry?

Check out Lies Pastors Believe, and listen to Hartman expound on these practices on Tool Talk: